20.12.2024

Euro Reform: Economic Urgency, Political Limbo

Tribune

8 septembre 2017

The German government’s wording has been tailored so that the most enthusiast fringe of commentators could still claim that the prediction of a euro completion was coming true. The political-economic reality of their approach points to quite a different direction though. Mr Schäuble’s idea to turn the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) into a sort of “European Monetary Fund” akin to the IMF seems to set a high bar for European cooperation, insofar as it likens this modest emergency facility to one of the most reputed global institutions. Beyond this first impression, the two German leaders have however dampened hopes of a different, more ambitious type of financial set-up. Angela Merkel has made clear that any common budget for the Euro zone should be “small,” not “hundreds of billions of euros,” thus directly rejecting Emmanuel Macron’s idea to commit “several percentage points of the area’s GDP,” i.e. hundreds of billions of euros…

Instability is inherent in a monetary union and can only be offset through close macroeconomic coordination and a damping mechanism based for example on fiscal transfers — the two of which seem to be out of reach in the European context. As many economists acknowledge, the single currency tends to amplify divergence, as it precludes, by definition, any adjustment in terms of exchange rates within the area. The underlying divergence can stem from various sources. Some of them are related to political choices; some are not.

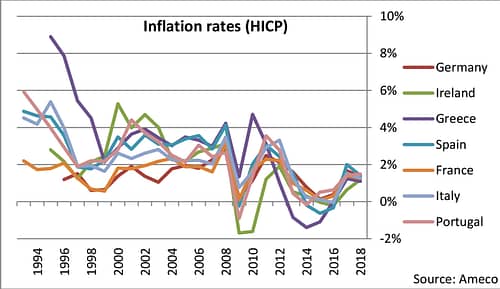

Most analysts point to differences in terms of national economic policies, especially labour policies, since the euro’s inception. Germany took steps as early as the early 2000s to pressure wages, while most other nations followed suit only when they were struck by the crisis or even later, as in the case of France, fifteen years after Germany’s reforms. Also, differences in terms of inflation rates have turned out to be a major source of divergence in competitiveness, as countries with higher inflation levels have seen their prices rise compared to the core. This is precisely what happened to peripheral countries throughout the 2000s.

Contrary to the urban legend, these countries did not experience any wage drift, as is clear from detailed unit labour costs statistics once inflation is taken into account[i]. In most cases, despite property bubbles and spending sprees that fuelled current account deficits, real wages barely rose at all throughout the euro’s first decade in these countries, and the same trend applied to productivity—a situation far from optimal of course. The divergence in competitiveness (in terms of nominal unit labour costs) resulted from Germany’s wage policy and from the persistence of contrasting inflation rates across the Euro zone. Inflation rates did converge to some extent from the 1990s, but they remained unsurprisingly different across the currency area throughout the 2000s[ii] – which means that prices actually diverged (…although at a declining rate of divergence).

Inflation rates have converged by and large since the crisis. This however has been achieved by suppressing demand and putting in place a generalized model of trade surpluses that are hardly sustainable for an economic area as a whole, especially since this shift does not rely so much on strong productivity gains as on depressed labour costs. Convergence cannot be enforced on the long term through a mere race to the bottom. The inflation gap, which could resurface after a genuine economic recovery, is not something that politics or even monetary policy can directly tackle in the long term, especially with a single central bank setting the same leading interest rates for nineteen heterogeneous economies.

On the other hand, the lack of macroeconomic coordination could technically be solved, but European politics is found wanting in this respect too. Gerhardt Schröder’s labour market reforms centred on decentralizing wage negotiations. At a time when wage growth in Germany is indispensable to achieving any kind of rebalancing in the euro zone, the political tools to encourage such a trend have become either inexistent or ineffective. Despite a situation not far from full employment, wage growth in Germany turns out to be subdued[iii]. And the German government does not appear willing to offset this trend with badly-needed investments, as it seems keen to maximize its budget surplus instead.

The only factor of convergence seems to be the still highly problematic situation faced by France and Southern Europe on the employment front – which exerts a downward pressure on wages, especially for younger workers. Similarly, differences in inflation rates have been suppressed since the crisis, not so much as a result of any true macro-economic convergence, as because of the recession and the pressure on labour costs.

The apparent convergence induced in Southern Europe by mass unemployment and collapsing birth rates hardly constitutes a long-term economic recipe for rebalancing — especially since affected countries have rushed to reorient their economic model towards exports of cheap products with little technological content. Since the crisis, national economies have further diverged on the technological front at a time when all European countries should embrace the ongoing industrial revolution (robotics, AI, 3D printing in particular). Many political leaders in Europe are perfectly aware of that situation. Despite their rather optimistic — at times ecstatic — rhetoric, fundamental worries resurface at regular intervals. French and Italian political leaders in particular therefore entertain the hope that the euro zone will evolve towards a model of fiscal transfers that would make up for the type of economic divergence inherent in a heterogeneous monetary union.

Mr Schäuble’s inexplicit proposal is not about transfers, but loans. These limited loans would be granted by the ESM in times of recession, in order to fund investments in affected countries, in exchange for stricter budgetary supervision. Despite the acknowledgment that more investments might be needed in times of economic hardship, this approach hardly signals a significant step towards the completion of the euro. A number of optimistic reports about his proposal, throughout Europe, did not even raise the issue of whether the Finance minister meant fiscal transfers or loans, thus ignoring a fundamental distinction around which nursery school conversations tend to revolve. (“Giving is giving; taking back is stealing” in the words of French pupils).

Rather than going to the bottom of their contrasting views, Europe’s political leaders have staged a conceptual convergence since the French election. They can only disappoint, since the gap that separates national public opinions and economic approaches precludes a definitive consolidation of the Euro zone at this stage. While fiscal transfers within the Euro zone are anathema to a vast majority of German voters, it remains illusory to expect any bold departure from that position, even after the federal election. As the episode of euphoria triggered by Emmanuel Macron’s election comes to an early end, the European Union is once again left with hard choices and insurmountable differences.

[i] https://www.robert-schuman.eu/en/doc/questions-d-europe/qe-289-en.pdf

[ii] See: Leila Simona Talani, The origins of the Euro-zone Crisis: The EMU and the loss of competitiveness, 2015, page 7, https://www.eui.eu/Projects/PierreWernerChair/Documents/MIKE-ARTIS/MikeArtiscommemorationpaper.pdf

[iii] https://www.ft.com/content/a34ebea0-4b66-11e7-a3f4-c742b9791d43