19.12.2024

Germany’s Energy Shake-Up and Russia-Turkey Tensions

Tribune

21 décembre 2015

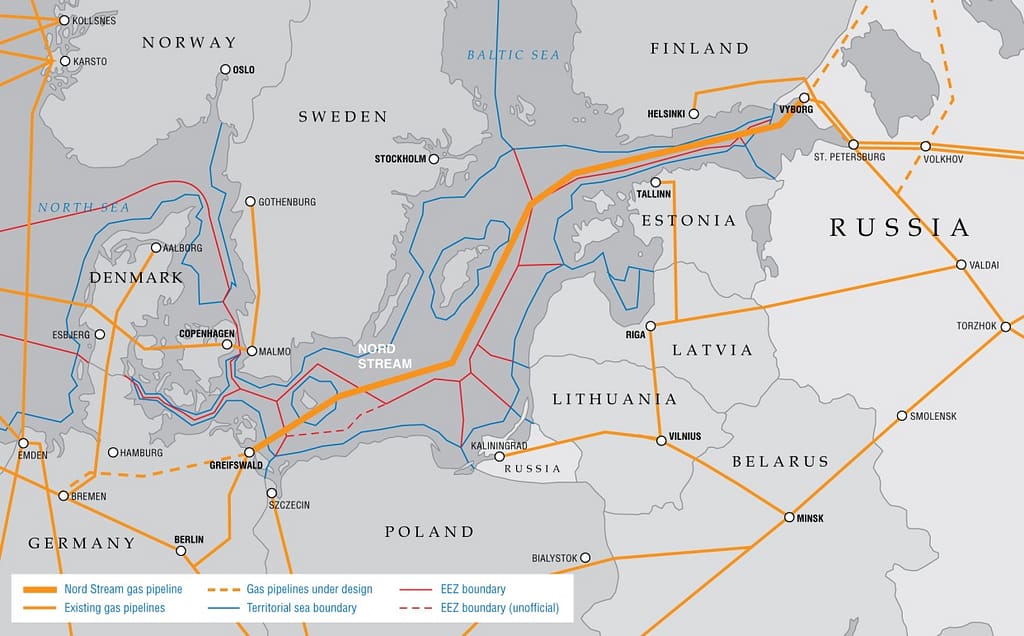

When Nord Stream was put forward by Vladimir Putin and Gerhardt Schröder—who shortly thereafter became Chairman of the operating consortium—it represented a turning point in the intra-European energy balance. Germany, the largest buyer of Russian natural gas, gained access, from 2012 onwards, to a direct flow of 55 billion cubic metres (bcm) of natural gas per year, from Russia through the Baltic Sea, thus bypassing the territories of its central European neighbours (see map in appendix 1). As this route has consolidated Russia’s role in EU gas imports, it has also made Germany all the more immune to disruption risks in Central and Eastern Europe. Although Central European countries are experiencing a high level of economic integration with Germany, Berlin guards against the possible impact of the strained relations between these countries and Russia on its gas imports. Consequently, the project known as Nord Stream 2, which consists in doubling the gas pipeline (therefore reaching a total capacity of 110 bcm while Germany consumed no more than 91 bcm in 2013) has implications far beyond the mere issue of the country’s gas imports.

Like Nord Stream, South Stream and Turkish Stream were intended by Russia to bypass Ukraine. South Stream was planned to run through the Black Sea—notably through Turkish territorial waters— to Bulgaria, while Turkish stream was planned to cross the Black Sea to reach Turkish Thrace (see map in appendix 2). Both options were also designed to compete with the rival European idea of a “Southern Corridor” (from Azerbaijan’s Caspian Sea coast to southern Europe through Turkey), and to secure new export routes to both southern Europe and Turkey. Meanwhile, Turkish Stream’s fate was all the more impacted by the competition from Nord Stream 2, since Germany, which has huge storage capacity, began to contemplate the idea of becoming a major gas hub for the rest of Europe, beyond merely securing its own consumption. The reasons leading to the cancellation or suspension of a major pipeline project are always complex. However, the link between the strengthening of the northern route and the suspension of the southern route cannot be ignored, even more so in a context where Russia tends to lengthily weigh competing options before making any final decision. Italy’s fierce opposition to Nord Stream 2 is yet another indication that the southern route as a whole is endangered by the northern one. Furthermore, as the negotiation of gas deals with China has further shown, Russia not only weighs export options at European level, but also increasingly, on the larger Eurasian scale.

Prior to Turkish Stream’s suspension, Russia’s intermediate step to lower the pipeline’s capacity from 63 bcm to no more than 32 bcm, despite its relative disappointment with China, signalled, as early as October, a genuine lack of interest in the Turkish option. Diplomatic relations between Russia and Turkey began to sour well before the Russian military aircraft was shot down. Meanwhile this trend did not halt the development, until recently, of ambitious projects, even in the nuclear sector. From the very beginning of the Syrian civil war, the two countries took diametrically opposed stances towards the Assad regime. However, cooperation on the Turkish Stream project began in 2014, despite already palpable tension. Their willingness to put the lid on their disagreement over Syria has recently reached a limit, but there is no indication so far that the acute diplomatic tensions that came to the fore during the second half of 2015 are the root cause of Turkish Stream’s suspension. Importantly, the idea of this pipeline had emerged in a context of severe tensions between Russia and the European Union over the Ukraine crisis. Conversely, the warming of relations between Russia and Germany, throughout 2015, seems to have been decisive in Russia’s disengagement from the Turkish route.

While Nord Stream 2 faces fierce opposition from most Central and Eastern European countries, Germany appears just as determined to carry out its plan. Germany’s political leaders strive, without great trouble so far, to neutralise the European Commission, which has agreed to deem Nord Stream 2 a “commercial project”[1] and to dismiss political objections. Hence, a specifically Russo-German partnership is emerging, as Germany partly overlooks the issue of gas supply diversification, a quest the Commission was supposed to spearhead. The Ukraine crisis, by raising awareness of the risks facing energy flows, could thus have, quite paradoxically, accelerated the rapprochement between Germany and Russia, against the background of the latter’s fascination for the former’s economic model. In the case of France, the appeasement with Russia was primarily motivated by the reassessment of the situation in Syria. As is often the case, Germany’s approach centres more on economic and energy issues. Germany currently pursues a bilateral strategy aimed not only at securing its imports of Russian gas, but also at developing its role as an energy hub, despite the collapse in commodity prices. If Nord Stream 2 eventually materialised, despite the significant opposition it is faced with, it would allow Germany to re-export more natural gas and, by charging transit fees to its European neighbours, reduce its national energy burden. This is precisely the strategy Turkey intended to pursue by means of an entente with Russia.

Appendix 1 : Nord Stream

Source : Gazprom

Source : GazpromAppendix 2 : Turkish Stream

Source : Gazprom (15/12/15)

Source : Gazprom (15/12/15)[1]« The first thing to say is that Nord Stream 2 remains a commercial project. And of course, it will be for commercial parties to decide which infrastructure is viable for them », Commissioner Arias Cañete at the European Parliament Plenary: opening and concluding remarks, Strasbourg, 7 octobre 2015.