20.12.2024

Eurozone Rebalancing: From Reality to Myth

Tribune

13 octobre 2015

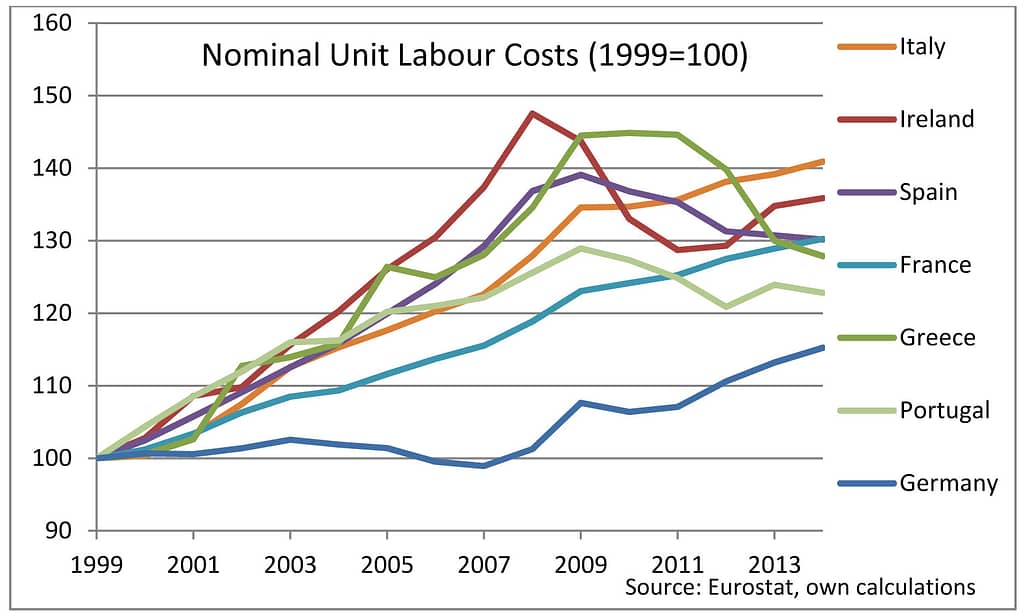

The belief in the feasibility of a transfer union relies on the notion that a certain level of convergence has re-emerged among Eurozone economies—reversing the diverging dynamics that had typified the lead-up to the crisis. Hence, transfer policies are chiefly regarded as an insurance mechanism in the event that a country is struck by a sovereign crisis once again, and not as endless flow of funds from Germany to impoverished southern Europe. This assumption is based on the assessment that while Germany has seen a rapid increase in its labour costs since the onset of the crisis, so-called peripheral countries have simultaneously experienced a sharp decline, leading to overall improvement in their competitiveness and trade balance. There is obviously some truth in this narrative, since Germany’s unit labour costs [2] have risen significantly since 2007. This came after a period of stagnation between 1999 and 2007 in nominal terms—which is an abnormal pattern given that inflation is included in the variable—and, consequently, a sharp fall in real terms, in the context of the political-economic strategy known as the “Agenda 2010”, which centred on lowering labour costs.

Will the trend of convergence continue or falter? Germany has experienced a stagnation of its productive investments—which echoes its deteriorating competitiveness—and a decline in its industrial production. This dynamic is at odds with the roaring economic powerhouse often depicted in the media. The situation in the labour market, which increasingly resembles full employment, and the trade surplus, which stands at about 7% of GDP, give a false sense of invulnerability. Lower labour costs, along with industrial outsourcing to Central Europe, has been central to Germany’s competitive strategy, aimed at spurring exports. Low unemployment has come as a result of this low-cost economic model. The reversal of the trend in labour costs has put this model at risk, particularly in a context of depressed global demand, with China’s turmoil further darkening Germany’s manufacturing outlook. The Volkswagen scandal adds to these worries and may act as game changer, as it now appears that the country’s leading industrial sector has followed a strategy that turns out to be highly perilous, from both a technological and financial perspective.

Although the government recently introduced a minimum hourly wage at €8.5, the economic headwinds facing Germany may undermine its acceptance of indefinite increases in labour costs that would endanger its economic model. The euro’s depreciation appears insufficient to make up for Germany’s deteriorating competitiveness. Many economists and political leaders across the globe have rightly called upon the German government to implement policies that would help reduce its massive trade surplus. Although these exhortations are legitimate, those who focus on wage policies usually underestimate the effect these would have on the country’s economic performance, in the current environment of weak growth and given its own weaknesses. Despite its huge trade surplus, the economy’s modest growth rate, over the last few years, has illustrated the vulnerability of an economic model that has so heavily relied on depressed labour costs to boost exports and now increasingly depends on domestic consumption. On top of the employers’ increasing worries with regard to wage growth, the government remains opposed, for the sake of its fiscal doctrine, to any rebalancing plan that would rely on public investment although such a strategy would both help reduce the trade imbalance and improve the growth potential after years of belt-tightening and misallocation[3]. As a consequence, Germany actually finds itself in a complicated situation, albeit far better than most of its Eurozone partners.

The refugee crisis, despite its short-term challenges, suddenly provides a long-term solution to Germany’s desperate labour shortage. Meanwhile this increased labour supply entices the country to resort once again to a strategy of wage devaluation. This temptation has recently been illustrated by the IFO institute’s recommendation to remove or lower the minimum wage in order to facilitate the migrants’ integration into the labour market, in the face of their allegedly low productivity. Against this background, Germany appears liable to reverse the trend of rising labour costs, in order to preserve its economic model affected by rising vulnerability. If the modest dynamic of convergence that has materialised since the crisis were to reverse, not only would it destabilise the Eurozone’s economy as a whole, it would also make the cost of a transfer union incredibly high.

At first sight, recent general elections in Greece and Portugal tend to signal a relative normalisation of the political situation in the Eurozone. In the space of one month, erstwhile leftist leader Alexis Tsipras was re-elected in Greece despite his about-turn over austerity while Pedro Passos Coelho, Portugal’s conservative pro-austerity PM, retained a significant lead over the centrist—similarly pro-euro but slightly less pro-austerity—Socialist Party. Despite a mixed electoral outcome in the latter case, both the Eurozone’s “black sheep” and “poster child” have reaffirmed a certain level of political commitment to the Euro’s logic. In this respect, the Eurozone’s establishment has proved particularly efficient in maintaining political cohesion—through various means—despite the currency union’s ugly economic record. Unsurprisingly, these achievements in terms of political manoeuvring have led to a new wave of economic denial. Rather than focus on unrealistic reforms of the Eurozone’s architecture, policymakers should address the massive economic imbalances, which result from the common currency, incompatible labour and fiscal policies between Germany and its partners, and the cult of housing bubbles. The current status quo over key macro-economic issues bears the risk of worsening the outlook for most countries, despite the relative upswing enjoyed by countries like Ireland, Portugal and Spain over the last couple of years.

Transfers would not make it for the large imbalances that threaten to grow again among Eurozone countries and aggravate their plight. It is of particular concern that most euro-enthusiasts ignore real economic issues and still devote themselves to pseudo-liberal posturing and flimsy administrative constructs such as the €55bn so-called “banking union.” A transfer union centred on support to peripheral countries—even if it were a realistic prospect—would not help make their economic model viable, let alone reverse the disastrous economic dynamic affecting major economies like France and Italy. Beneath superficial statistics, these countries are experiencing a full-blown slump and are increasingly turning into countries of emigration for their younger citizens, due to the lack of economic activity and opportunities. The fashionable institutional reforms advocated by technocratic circles are out of touch with reality and would not help bring these economies back to life. The fact that younger generations bear the brunt of economic hardship unfortunately enables thoughtless politicians to indulge in technocratic romanticism.

[1] See for example: “Macron Calls for Radical Reforms to Save Euro”, FT, 24 September 2015

[2] Unit labour costs represent the ratio between the country’s total wage bill and real GDP. ULCs similarly represent the ratio between the average wage and average productivity.

[3] This strategy has been advocated by some German economists like Marcel Fratzscher.