27.06.2024

60th Anniversary of France’s Recognition of the People’s Republic of China : Are Franco-Chinese Relations Seeking Balance ?

Interview

26 janvier 2024

January 27th 2024 will mark the 60th anniversary of France’s recognition of the People’s Republic of China, and will be an opportunity for the two countries to communicate on their cooperation. What was the background to this recognition in 1964? As this anniversary takes place against a backdrop of geopolitical instability and changes in the balance of power between the two countries, what is the current state of diplomatic, economic and cultural cooperation between France and China? How does the development of bilateral relations between France and China fit in with France’s Asia-Pacific strategy, and what are the issues at stake? How is the Sino-French relationship likely to evolve in this respect? Emmanuel Lincot, a researcher at IRIS specialising in the political and cultural history of contemporary China, takes a closer look.

What was the background to France’s recognition of the People’s Republic of China in 1964?

This recognition took place against the backdrop of the Cold War, at a time when General de Gaulle, finally free of the colonial burden, was trying to open up a third way. The Chinese, for their part, had severed their relations with the USSR and were also looking for support. Finally, since the Bandung Conference in 1955, China has been keen to seize leadership of the Third World, which would be damaging to French interests in Africa in particular. But what better way than to channel these excesses by recognising Beijing? Recognition of the People’s Republic was envisaged as a way of pulling the rug out from under Beijing. This foreign policy imperative also had another objective: to better control French extreme left-wing youth, who were already ready to revolt and had broken with the French Communist Party. With this recognition came the romance of a consensual figure, André Malraux, then Minister of Cultural Affairs, who, symbolically speaking, established an imaginary link between his own generation and these young people who had embraced the revolutionary ideas inspired by Beijing, the new Mecca of international communism opposed to Moscow. Last but not least, de Gaulle wanted to regain greater diplomatic latitude in relation to Washington, which he had supported unwaveringly during the crisis that had pitted the Western world against the Soviets two years earlier with the Cuban missile crisis. It also knows that Beijing is capable of acquiring nuclear weapons. How can you not recognise a country that has the bomb? How could anyone fail to recognise a country with a population of 600 million? This recognition was preceded by trips made by a number of leading figures. The couple Sartre Beauvoir, but also the parliamentarian Edgard Faure or the actor Gérard Philippe… There is a real sympathy of the French for China. This rather favourable image is linked to relations that go back centuries and were supported under the old regime by the mediation of the Jesuits. It counterbalanced a more negative image conveyed by the former soldiers of Indochina who had had to fight the Vietnamese communists aided by the Chinese, as well as the Catholic clergy who, until the establishment of the communist regime in 1949, owned dioceses on the Chinese mainland as well as considerable real estate, the use of which had been taken away from them following the expulsion of their missionaries and priests. However, De Gaulle did not establish these links with Peking lightly. He commissioned two of his loyal followers (Generals Pechkoff – nephew of Maxim Gorky, who had rallied to the cause of the White Russians and then the Free French – and Guillermaz – a sinologist, a great specialist in the Chinese Communist Party and future founder of what was to become the first chair of contemporary Chinese studies at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales) to announce his decision to Chiang Kai-shek himself, who was taking refuge in Taiwan at the time. As the initiator of the French policy of recognising « one China » (Peking in this case), which Paris has maintained for sixty years, it is important to debunk the cliché constantly repeated by the French and the Chinese that France was the first Western country to recognise the People’s Republic of China. Other countries, such as Great Britain, did so before France. The Cultural Revolution in China brought this initial rapprochement with France to a screeching halt for almost ten years. It was not until several decades later, during the Jacques Chirac / Jiang Zemin years, that bilateral relations really began to improve at the end of the 20th century, after overcoming a major crisis: the Tiananmen repression (1989) and the arms sale to Taiwan (Mirages 2000 and Lafayette frigates) initiated by François Mitterrand.

Sino-American rivalry, conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East, China’s influence on the African continent, elections in Taiwan… this anniversary is taking place in an unstable geopolitical context. At a time when the balance of power between the two countries has shifted, what is the current state of diplomatic, economic and cultural cooperation between France and China?

At a time when anarchy seems to have become the norm in the world, it is important to focus on a few anniversaries. They serve as landmarks. The recognition of the People’s Republic of China is one, but another will be celebrated in June: the Normandy landings. These dates provide a framework and breathing space for an international agenda that is often in turmoil. As far as Franco-Chinese cooperation is concerned, it is important in areas where France excels: aeronautics (consider that China’s medium-haul aircraft, the Comac 919, owes much of its engineering to Safran and Thalès…) with the creation of a second Airbus assembly line in Tianjin, the luxury goods industry, agri-food (this last sector still accounts for an insufficient share of bilateral trade), education with, in Paris, the symbolic opening of the Maison de la Chine – Jardin de l’harmonie at the Cité universitaire (14th arrondissement), which will accommodate 300 students on the campus of the Cité universitaire. However, as we all know, this relationship has become asymmetrical, with France clearly losing out, as the very short-term import of BYD cars into Europe, for example, poses a challenge to a whole section of our automotive industry. For the sake of balance, France has opened up more economically to the « other » China: Taiwan. In this context, it will be welcoming ProLogium, a major electrolyte battery factory, to the Dunkirk region. This French pragmatism in its choice of partners corroborates a situation that can be observed everywhere in the world: the pursuit of nations’ strategic interests is more often than not at odds with their economic interests. In the strategic arena, France and China maintain a dialogue that differs from that of the US and Washington, whose stance, on the other hand, is deliberately confrontational.

How does the development of bilateral relations between France and China fit in with France’s Asia-Pacific strategy, and what is at stake? How is the Sino-French relationship likely to evolve in this respect?

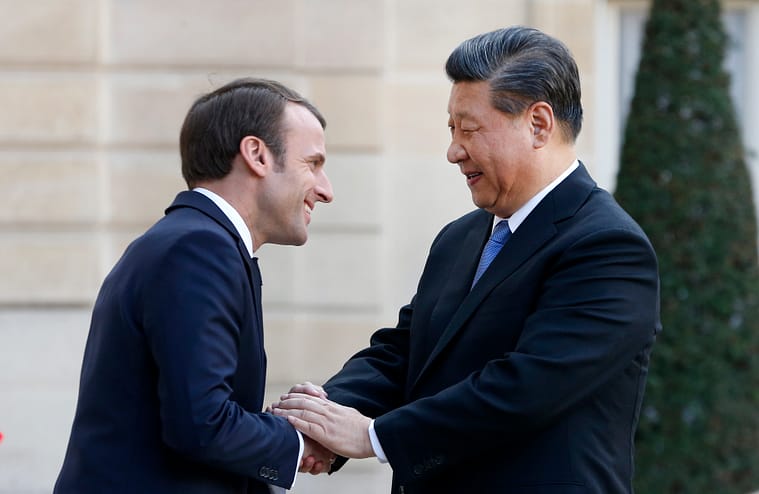

The innovation concerns the strategic dialogue between the Southern Theatre of the People’s Liberation Army and the French Forces Command in the Asia-Pacific (ALPACI) to strengthen security and regional cooperation. This should be seen as an inclusive approach towards China. I also see it as a reversal of the French position following the slap in the face inflicted by Australia, which, under pressure from the AUKUS, denounced the order for French submarines. Furthermore, the Indo-Pacific as conceived by the French and Europeans does not exclude economic partnerships with China. This is the principle of the Global Gateway and, for France, a desire to establish genuine cooperation with China in the field of biodiversity conservation. Furthermore, the two countries are committed to pursuing a high level of ambition in line with the Beijing Call to Action launched in November 2019 and within the framework of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and its Paris Agreement, as well as the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (hereinafter referred to as the « Kunming-Montreal Framework »), whose adoption at the second part of the Convention on Biological Diversity (COP15) is welcomed by both parties. China, which will hold the presidency of COP15 for the next two years, intends to work actively with France to ensure full and effective implementation of the Kunming-Montreal Framework. In short, France wants to maintain a more balanced, cooperative relationship with China, but one that is at arm’s length from the strategic choices made by Washington against Beijing. A sign of the times: Xi Jinping is due to make a state visit to France in the coming months.

Translated by Deepl.